As the son of a doctor, Sangu Delle grew up around healthcare. He spent much of his childhood in medical facilities, surrounded by doctors and nurses. After completing his higher education overseas —studying business at Harvard and then law at Oxford—he found himself drawn back to both Africa and healthcare.

As the CEO of Africa Health Holdings, Delle now spends his days tackling the continent’s biggest healthcare challenges. The company aims to build high quality, effective, and sustainable healthcare systems in Africa.

Africa Health Holdings was initially created as a spin off from another of Delle’s ventures, Golden Palm Investments. An impact investment firm, Golden Palm originally invested in a variety of sectors, including agriculture, technology, real estate, healthcare, and more. As the firm’s portfolio grew, Delle and his team saw an opportunity to launch a new company focused exclusively on strengthening Africa’s healthcare infrastructure while narrowing the focus of Golden Palm Investments to the tech sector.

Prosper Africa recently spoke with Delle on how he hopes to shape Africa’s healthcare future and the opportunities he sees in a post-COVID world.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What’s the problem that Africa Health Holdings is trying to solve?

Delle: At Africa Health Holdings, we’re building Africa’s healthcare future. Today, Africa has 14 to 15 percent of the global population, yet we’re disproportionately responsible for almost a quarter of the global disease burden. We also only account for three percent of global healthcare workers, and only one percent of the global healthcare expenditure. So we already have a massive supply-demand problem.

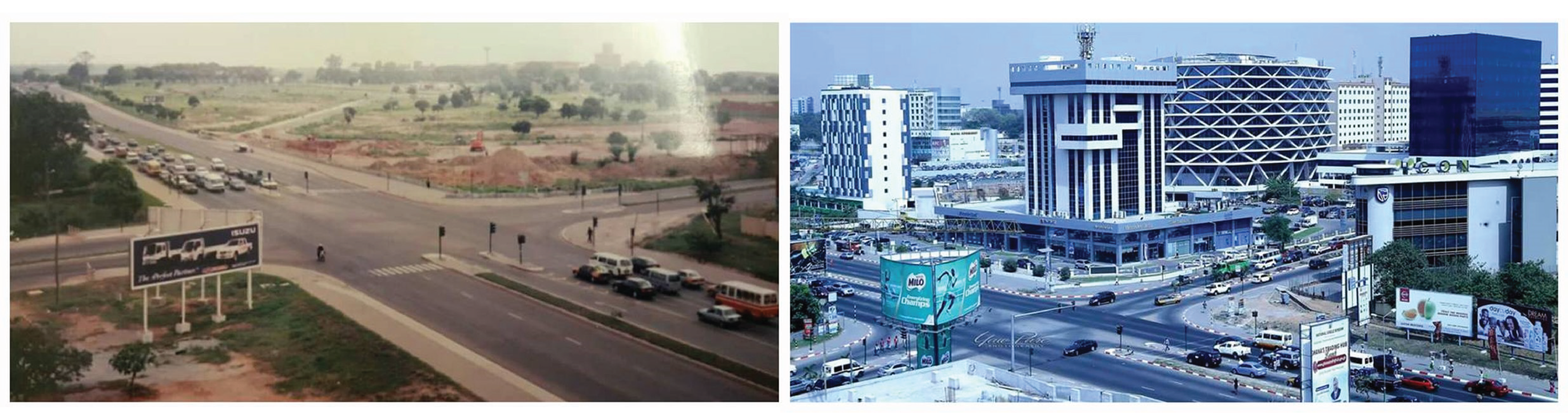

Now lay on what’s happening with our demographics: our population is doubling over the next three decades. In 30 years, literally one out of every four people on the planet will be African. From that perspective, we have a big healthcare problem. Not only is there an imperative to solve the healthcare problems of today,we also have an imperative to build our healthcare system differently and to scale it given this demographic explosion that’s about to happen, where we’re going to see a massive growth in population coupled with urbanization.

That creates all sorts of challenges but within it opportunities. So we’re solving the healthcare challenges we have now, but scaling healthcare systems up and pioneering innovative models that allow us to not just catch up with the present but to build for the future.

What kinds of innovative models are you pioneering? How do they address that healthcare supply-demand challenge facing the African continent?

Delle: We very much think of ourselves as a technology-enabled business. We ask ourselves, ‘How can we leverage technology to better deliver care?’ And we’ve approached that in a number of ways. Pre-COVID, we had invested in a telemedicine product that was end-to-end and helped meet patients’ needs. However, from an access perspective, this didn’t actually solve the problem. Most telemedicine solutions require a smartphone and data. While Africa has over a billion mobile subscriptions, many people can’t afford the data.

In theory, telemedicine sounds like a great thing for democratizing healthcare, but in practice, it actually just creates new digital haves and digital have-nots. So we went back to the board and asked. ‘Okay, how do we innovate differently to solve the access problem?’ That’s how we came up with a hybrid model—bringing telemedicine inside micro clinics.

We piloted the program in rural Ghana. These micro clinics had just one employee, a nurse. Patients would come in, and the nurse would do the diagnostics. The nurse then takes the patient to the next room where there’s a computer screen and a doctor on the line. You have the nurse here to run tests, and you’re also getting a virtual consultation with the doctor. And if you need a prescription at the end, you can pick up your medicine from the nurse on your way out. If the micro clinic doesn’t have that medication, then the pharmacy can deliver it to you.

Suddenly, hard-to-reach areas are connecting to the healthcare system. Before, a doctor would’ve had to travel to these regions, which is expensive and time-consuming. Now all of that is eliminated because a doctor can sit in Accra and do consultations anywhere. Patients loved it because they’ve been able to get the care that they need, and they see the clinical results. They don’t have to worry about having enough data.

And so that’s a different way in which we’ve approached telemedicine. Because a lot of times these ideas and these innovations sound good, but once you take them out of a Silicon Valley context and apply it to the idiosyncrasies of the realities of dealing in our markets, then you realize that you can’t do a cut-copy-paste model.

Has COVID-19 played a role in how folks have responded to some of these micro clinics or was that demand there even pre-COVID?

Delle: I think that it’s actually a mix of the two. On the one hand, that demand was there already. And I think that irrespective of COVID, you would have had some uptake here. But I do think COVID has sharply accelerated the growth of digital solutions. I think that a lot of people that ordinarily are not very comfortable with technology, or would have resisted technology, suddenly had no choice because of COVID. COVID forced everybody to use mobile money and utilize digital solutions because there was no other option. That has helped, in general, with improving the adoption and the understanding of some of these technological innovations.

What do you see as the next big opportunities? What do you have your eye on in the health space over the next year?

Delle: My goal as CEO is to think about that future and to plan for that future. While the team is spending time managing the day-to-day and improving operations, I’m spending my time figuring out what the future might look like. For example, we already know that Africa has a massive healthcare workers shortage with only three percent of global healthcare workers. We can improve that, but if we invested $10 billion in educating future healthcare workers right now, we won’t see the impact for another 15 years. It takes time to get through university, medical school, and residency. How do we catch up in the interim?

We’ve been exploring how we can leverage emergent technologies like machine learning and artificial intelligence. There’s a need to ensure that these AI technologies actually are tested against proper data sets that are reflective of the communities in which we’re going to be working in. Take dermatology for example. Skin-related diseases are in the top five of Ghana’s disease burdens. But we have less than one dermatologist per one million people in the entire country. Can we train algorithms against these data sets to make some preliminary diagnosis and start bridging this healthcare access gap? That’s been a big focus for me.

What advice would you give an investor exploring the healthcare space in Africa?

Delle: First, I think people need to abandon certain preconceived notions about what business models should look like and instead really figure out what actually works for this context. Look at this delineation between pure tech and hybrid. A lot of these pure tech models—outside of maybe FinTech—very rarely work. I’ve found that most businesses have to take a more hybrid approach to be successful.

The second thing I would say is—I think that our market is an interesting market in that it’s not necessarily the best ideas that win but the best capitalized ideas. Because the supply-demand imbalance on the capital side is so significant and the disparities are so huge, I’ve seen situations where having access to capital in-and-of itself gives you a competitive advantage. I would say it’s important to acknowledge the inherent inequalities in the funding ecosystems. We know from the data that a lot of capital in East Africa, for example, does not go to African founders. We also know that if you look at everyone who’s raised over a million dollars across the African continent, women are significantly underrepresented. I think it’s important for us to be upfront about these issues. As investors, we cannot just sit and say, ‘This is a pipeline problem.’ Instead, we need to say, ‘What role can we play in fixing that? How do we ensure that we’re not just providing capital, but we’re thinking about the inclusivity of that capital funding process?’ We have to ensure that the roles we’re playing as capital providers aren’t perpetuating neo-colonial models and that we’re not perpetuating gender inequalities in our approach.

Read more interviews and stories featuring investors and business leaders in the Prosper Africa Blog.